Destroyed evidence, a flaky witness and a mistrial: how a Canadian woman's killer evaded justice for 40+ years

They pulled him over as he was heading to work.

Michael Glazebrook was stopped at a traffic light, window rolled down as Det. Arras Wilson of the Monterey County Sheriff’s office in California walked up to his vehicle with a search warrant for his DNA.

- Is the full episode above failing to play? You can watch it here

“You got time for me to check with my lawyer?” asked Glazebrook, a local school bus driver.

“No… You don't have no right to talk to an attorney first, that's what a search warrant is for,” said Wilson in a 2021 police recording of this interaction, obtained by W5.

Wilson was working on the cold case homicide of Sonia Herok-Stone, a Canadian from Montreal. Herok-Stone had been murdered in 1981 shortly after moving to the small California community of Carmel-by-the-Sea with her daughter.

Glazebrook was the prime suspect in the 1980s, and 40 years later he was once again the focus of the police investigation.

“I’m taking a fresh look at the case and I'm doing what I can to solve this case… It’s also really important for me to not just catch the person who did it, but to eliminate anybody who isn't involved,” he said to Glazebrook.

If the DNA was a match, it would bookend decades of investigative work pockmarked by a seemingly endless array of setbacks that included destroyed evidence, a flaky witness, and a mistrial — and a generational struggle for the Stone family to get a killer who evaded justice behind bars.

The crime and the cut

When detectives arrived at Herok-Stone’s home in 1981, they found her body blocking the front entrance doorway, partially naked and bloodied — with a pair of pantyhose tightly tied around her neck.

The 30-year-old had been strangled to death.

The exterior of Sonia Herok-Stone's home in 1981 (W5, supplied photo)

The exterior of Sonia Herok-Stone's home in 1981 (W5, supplied photo)

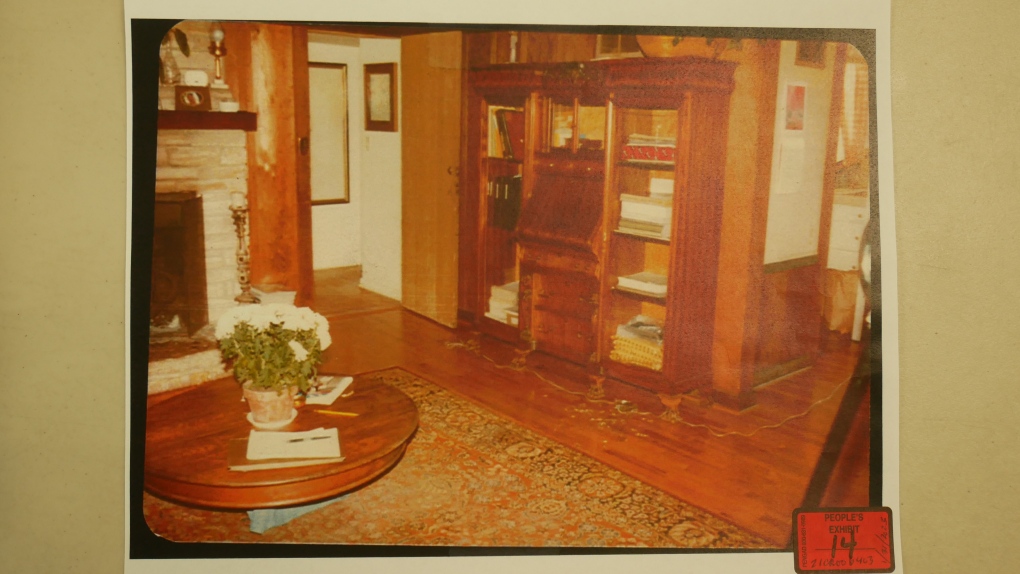

Interior of Sonia Herok-Stone's home in Carmel-by-the-Sea, in 1981 (W5, supplied photo)

Interior of Sonia Herok-Stone's home in Carmel-by-the-Sea, in 1981 (W5, supplied photo)

“She slowly died,” said Lins Dorman, one of the first detectives from the Monterey County Sheriff’s office on the scene in 1981.

It was evident, based on what Dorman saw, that the culprit “kneeled over her with his face inches away from hers taking her pantyhose… pulling tighter and tighter and tighter.”

“This was a violent, violent attack,” he said.

Mugshot of Michael Glazebrook (W5, supplied photo)

Mugshot of Michael Glazebrook (W5, supplied photo)

By the next day, Glazebrook was a prime suspect.

He was 25-years-old at the time, married and a tradesman who had been discharged from the navy — and lived right across the street.

Det. Dorman, who had been canvassing the neighbourhood with his partner the day following the murder in 1981, approached him while he was fixing a boat in his yard.

They asked him to remove a mask covering his face.

“I'm immediately drawn to his right cheek,” said Dorman. “He's got this deep red scratch… just under his eye… running down his right cheek, his jawbone and then it slowly fades into his neck.”

There was blood underneath Herok-Stone’s left ring fingernail — a strong indication, investigators believed, that she clawed at the killer moments before her death.

And that cut on Glazebrook’s face was coincidentally on the same side investigators found material under Herok-Stone’s left hand.

Blood can be seen underneath Herok-Stone’s left ring fingernail. (W5, supplied photo)

Blood can be seen underneath Herok-Stone’s left ring fingernail. (W5, supplied photo)

Glazebrook claimed he got the gash while cutting plexiglass, but Dorman noted in his 1981 report there was no sign of blood in the work area.

And his stories also kept changing: first he said he was at his father’s house at the time of the murder, then claimed he had gone to the hospital to deal with the cut on his face and stayed overnight.

He maintained he didn’t know Herok-Stone.

“He was fidgeting. He was hemming and hawing… I'm thinking, boy, this guy is really nervous,” said Dorman. “I said, ‘Oh, this could be our guy.’”

The admission and the crucial error

As suspicions mounted, Dorman and his partner devised a plan to bring Glazebrook into the police station for a series of outstanding traffic warrants.

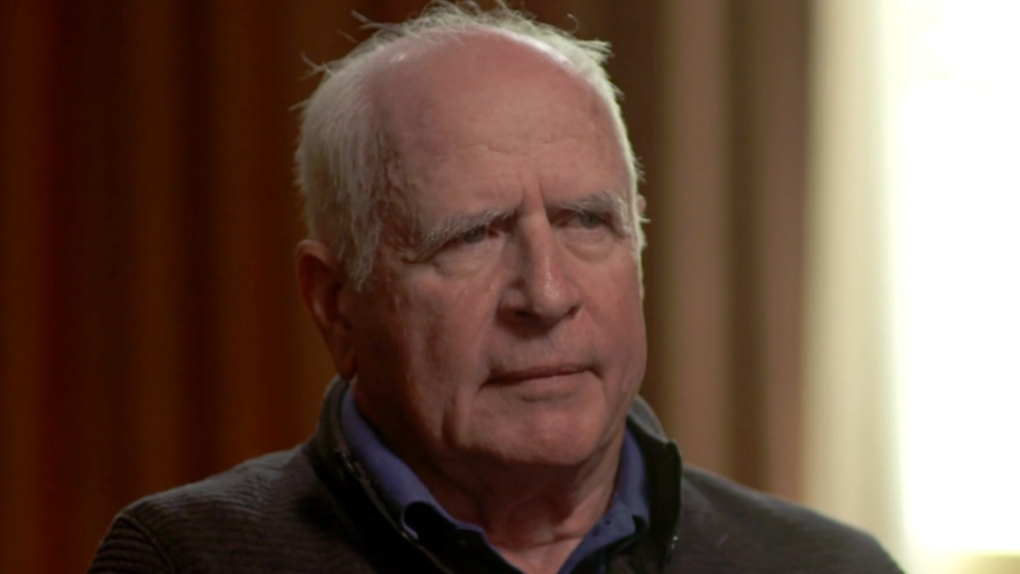

Det. Lins Dorman speaks with W5.

Det. Lins Dorman speaks with W5.

He was booked, fingerprinted and photographed. The key was to get a mugshot of his face with the cut on it.

He agreed to do a blood test that ended up matching the blood under Herok-Stone’s fingernail. (ABO blood tests were helpful but not conclusive and could only eliminate roughly 70% of the population.)

Then upon further questioning came a blockbuster admission: Glazebrook now claimed to have been having an affair with Herok-Stone and was at the house the day of the murder — but denied killing her.

“I'm convinced that's the killer,” said Dorman.

In 1982, Glazebrook was charged with first-degree murder.

Bob Moody, a deputy district attorney who was the lead prosecutor in the trial, said he "felt good" with the case they had.

“He had said earlier that he'd never been in her house. Now he puts himself there,” said Moody. “That's huge…That's the ball game.”

But just as quickly as they narrowed their sights on Glazebrook, the case began to unravel.

Prior to the trial — a judge ruled Glazebrook’s admission that he was at Herok-Stone’s place the day of the murder was inadmissible due to police misconduct. The Monterey County Sheriff's office had violated his rights, having picked him up on traffic warrants instead of murder charges.

They lost Glazebrook’s statement.

“It's like I'm going into a heavyweight fight with one hand tied behind my back,” said Moody. “This is really blockbuster evidence.”

The star witness

Despite this setback, Moody and his team went into the 1983 trial with an ace up their sleeve: a star witness.

A woman Glazebrook had been having an affair with had come forward alleging that he had confessed he had been at Herok-Stone’s place the day of the murder.

“It's an independent verification that he was, in fact, in Sonia Stone's house the morning she was killed,” said Moody. “It's huge.”

But shockingly — she recanted her story.

Glazebrook’s girlfriend, according to Moody, told the court that police had been leaning on her and that she made up the story because she was mad at him.

Bob Moody, a deputy district attorney who was the lead prosecutor in the trial, speaks with W5.

Bob Moody, a deputy district attorney who was the lead prosecutor in the trial, speaks with W5.

“This is really bad,” said Moody. “This is a major blow to the case.”

To make matters worse, the day they brought in Glazebrook to get a mugshot with the cut on his face, the camera failed to operate.

They had no photo of Glazebrook with the gash.

The trial ended in a hung jury, with nine jurors voting to acquit.

Glazebrook was now a free man.

Degraded DNA

By 2009, Dorman had retired but a new detective from the Monterey County District Attorney’s office was assigned to the case.

And investigators had a tool they didn’t in the '80s — DNA testing.

In 2010, Josh Sehhat, a forensics expert and criminalist at the California Department of Justice, started doing tests on the evidence, including the blood from Sonia’s fingernails.

The sample had the profile of male DNA.

The goal was then to cross-reference that male DNA with a sample of Glazebrook's DNA — which had been stored in blood vials roughly 30 years ago.

But at some point over the years, those vials broke — and had spilled onto the same envelope where Sonia’s fingernails had been kept.

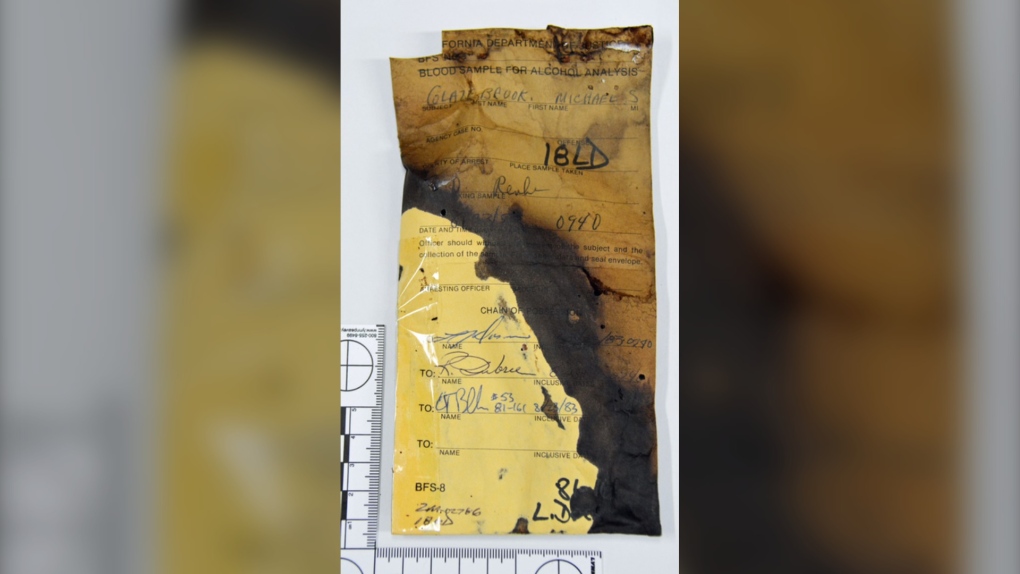

The DNA from that envelope covered in Glazebrook’s blood was so severely degraded, the forensics expert could only generate a faint male profile from it (W5, supplied photo)

The DNA from that envelope covered in Glazebrook’s blood was so severely degraded, the forensics expert could only generate a faint male profile from it (W5, supplied photo)

Setting aside the possible contamination of Sonia’s nail clippings with the broken vials — the DNA from that envelope covered in Glazebrook’s blood had been so severely degraded, Sehhatt could only generate a faint male profile from it.

“All the DNA kind of degraded to a point where it wasn't useful,” he said.

Ultimately, the tests did show that there was male DNA in both samples.

“I’m thinking it could be [Glazebrook] but I don't know for sure,” said Sehhat.

Josh Sehhat, a forensics expert and criminalist at the California Department of Justice, speaks with W5.

Josh Sehhat, a forensics expert and criminalist at the California Department of Justice, speaks with W5.

In order to get more certainty, they needed a new DNA sample from Glazebrook.

But the Monterey County Sheriff's office — lacking funding and resources — aren’t able to procure another DNA sample from Glazebrook and the case was once again shelved in 2013.

'One in 46 quadrillion'

In 2020, the Monterey County District Attorney created a task force focusing on dozens of cold cases where DNA evidence was available.

Det. Wilson was assigned to the Herok-Stone case and believed right away it “was still very solvable.”

Det. Lins Dorman (left) with Det. Arras Wilson of the Monterey County Sheriff’s office in California (W5)

Det. Lins Dorman (left) with Det. Arras Wilson of the Monterey County Sheriff’s office in California (W5)

But tackling a nearly 40-year-old unsolved murder had its unique challenges — from tracking down witnesses who had moved or since passed away, to locating evidence stored away and forgotten about — it wasn’t going to be easy.

It was also critical to figure out whose DNA was under Herok-Stone’s fingernail. That meant going back to Glazebrook to get a new DNA sample.

By this time, Glazebrook was in his 60s and — from the outside — looked like an upstanding member of the community. He was a little league umpire, coach and school bus driver.

Top and bottom: File photos of Michael Glazebrook, who became a little league umpire, coach and school bus driver (W5, supplied photos)

Top and bottom: File photos of Michael Glazebrook, who became a little league umpire, coach and school bus driver (W5, supplied photos)

A search warrant was issued for a DNA sample from Glazebrook in early 2021 and after swabbing his mouth in Wilson’s vehicle — the sample was sent for testing.

“It determined that the blood under [Herok-Stone’s] fingernail was Michael Glazebrook with the odds of it being anybody else other than Michael Glazebrook one in 46 quadrillion,” said Wilson.

A quadrillion is one million billion.

Investigators had a breakthrough.

In August 2021, Glazebrook was, for the second time, charged with first-degree murder in the killing of Sonia Herok-Stone.

Knowing the potential weakness in their case due to the possible blood contamination (it was later determined there was no contamination), Wilson spent months painstakingly trying to procure an additional DNA sample from a series of breast swabs in Herok-Stone’s 1981 sexual assault kit.

Upon further testing — the DNA profile generated from those breast swabs were consistent with Glazebrook's. They now had two samples of Glazebrook’s DNA from Herok-Stone’s body.

“It really cracked the case,” said Wilson. “And it was the last thing that we needed to be able to prove to a jury beyond any reasonable doubt that Michael Glazebrook was the killer.”

In June 2023, Michael Glazebroook, shown in a prison jumpsuit in court, was convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to life in prison with no chance of parole for the murder of Sonia Herok-Stone (W5).

In June 2023, Michael Glazebroook, shown in a prison jumpsuit in court, was convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to life in prison with no chance of parole for the murder of Sonia Herok-Stone (W5).

This past June, 67-year-old Glazebroook was convicted of first degree murder and sentenced to life in prison with no chance of parole.

Decades after the murder, there was no confession. No apparent remorse.

And even as Glazebrook sat in Det. Wilson’s car providing that fateful sample of his DNA in 2021, he still couldn’t keep his story straight.

“So did you even know her at all?” asked Wilson, knowing he had told police in the ‘80s he’d been having an affair with her.

“No,” he said. “Never even met her.”

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

Czechia scores late to eliminate Canada from world juniors

Jakub Stancl scored his second goal of the game with 11.7 seconds left in third period as Czechia survived a blown 2-0 lead to defeat Canada 3-2 and advance to the semifinals at the world junior hockey championship on Tuesday.

Canadian couple lives on cruise ships — with no plans to return to land

With 75 countries and territories visited, a retired Canadian couple is making the most of life as they cruise full-time, from coast to coast. They're part of a growing trend of people opting to retire at sea.

Planes catch fire after a collision at Japan's Haneda airport, killing 5. Hundreds evacuated safely

A passenger plane and a Japanese coast guard aircraft collided on the runway at Tokyo's Haneda Airport on Tuesday and burst into flames. Transport Minister Tetsuo Saito confirmed that all 379 occupants of Japan Airlines flight JAL-516 got out safely before the plane was entirely engulfed in flames.

BREAKING Israeli strike in Lebanon kills senior Hamas official Saleh al-Arouri: security sources

Senior Hamas official Saleh al-Arouri was killed on Tuesday night in an Israeli drone strike on Beirut's southern suburbs of Dahiyeh, three security sources told Reuters.

A missing person with no memory: How investigators solved the cold case of Seven Doe

Police specializing in missing people and cold cases have discovered the identity of a woman with no memory in one of the most unusual investigations the sheriff's office has pursued and one that could change state law.

Tim Hortons reveals which three doughnuts will join Dutchie in returning to menu

Tim Hortons has revealed which three retro doughnuts will join the Dutchie in returning to its menu next week.

Weight-loss drugs: Who, and what, are they good for?

Extraordinary demand, and high prices, for powerful weight-loss drugs will keep them out of reach in the coming year for many patients who are likely to benefit.

Woman who fell out of Edmonton city bus dies

A woman who fell out of an Edmonton city bus Friday has died, police said in a media release issued Monday.

Canada's 100 highest-paid CEOs broke new compensation records in 2022: report

Canada's 100 highest-paid CEOs broke records with their compensation in 2022, according to the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives.